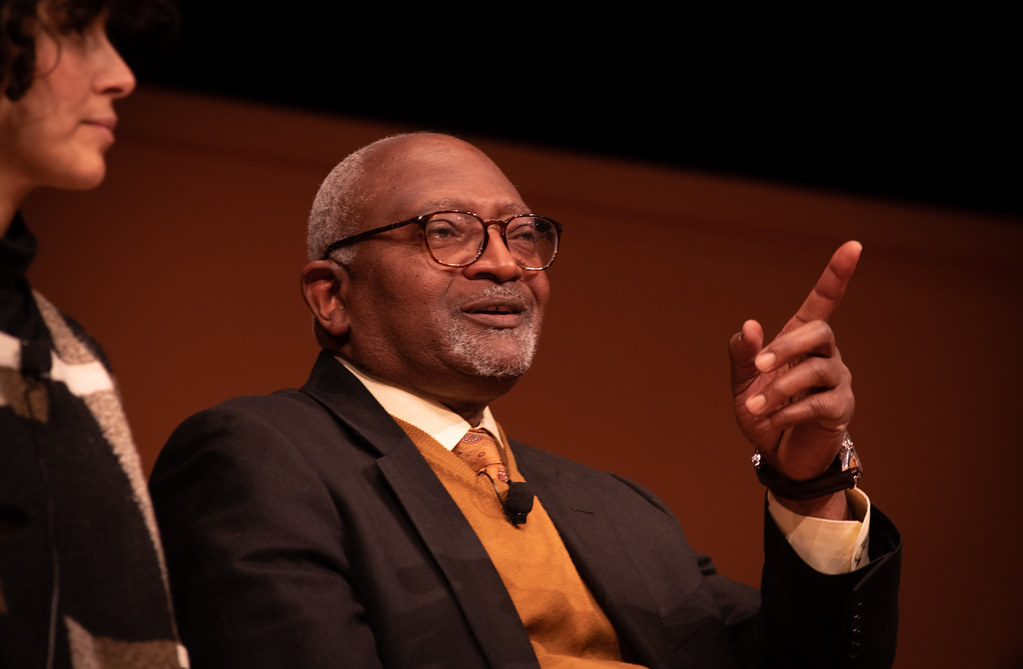

The Torch had an opportunity to interview via Zoom Dr. Robert Bullard. Bullard has been at the forefront of environmental justice for over 40 years.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in South Alabama, in a small-town named Elba. It’s right on the bottom of the state, close to Florida.

So what led you on this journey? The global justice, or the social justice journey?

Well, I was asked to collect data for a lawsuit that my wife had filed back in 1979 —Bean v. Southwestern Waste Management Corp. And she needed someone to gather the data for her lawsuit. The first lawsuit in the US to challenge environmental racism, using civil rights law. I’m a trained sociologist, and a lot of my research focuses on housing and residential patterns. And so I just, basically transferred my skills to look, instead of looking at housing discrimination, looking at environmental discrimination. I had 10 students in my research methods class at Texas Southern University, and I designed the study. We basically mapped where all the landfills, incinerators, and garbage dumps are located in Houston. This was back in 1979.

When did you realize that you had made a difference?

You know, it was something that I didn’t plan on. The trajectory of my career was something that just happened. When I looked at the study data in Houston 41 years ago, the results and the findings were glaring. But this federal judge said this was not discrimination. We found out that 100% of all the city-owned landfills were located in Black neighborhoods. Six out of eight of the city-owned incinerators were in Black neighborhoods. And three out of four of the privately-owned landfills were in Black neighborhoods. From the twenties up until 1979, 82% of all the garbage dumped in Houston was dumped in black neighborhoods even though blacks only made up 25% of the population. After that, Judge [McDonald] said, “This was not discrimination.” Being a sociologist, I want to know: if this is not discrimination, then what is? So I expanded the Houston study to look at the southern United States, and I found the same pattern across the southern United States. That’s how the book, Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality came about in 1990. There were no studies that looked at these issues, and there were no books on this. My book was the first book. My thing is, why is this so invisible? Why is it such a glaring form of racism, but there’s hardly anything written about it? And I knew right then and there that would be the area I would focus on in my research. And it has been the focus of my research since.

Where in the US is change needed the most?

If you look at how pollution and environmental degradation will map closely with race. In the areas where you have lots of housing discrimination and residential segregation and other forms of disenfranchisement for people of color, you’ll find that’s where you have the greatest concentration of environmental injustice. Whether it’s in the southern United States with African-Americans, on the US Mexican border with Latinos, or in the planes in terms of Native Indigenous folks. The fact is that systemic racism will drive pollution in the direction of the path of least resistance. Historically, that has meant poor people and people of color because of how policies are made and how the laws are enforced or not enforced. You’ll see that you could map this in a way that it’s very clear, very systematic, and in many ways, very intentional. Not accidental, not coincidentally, but very intentional.

So I’d say if you talk about regions, the southern United States is a region that has the most egregious forms of environmental racism because of the legacy of Jim Crow, of the Confederacy, and resistance to civil rights, equal protection, lax enforcement of environmental laws, et cetera. So you can see a pattern that will just stick out. Then you start looking at cities and rural areas. You look at states that have small people-of-color populations. I say in Oregon, you’ll find that the people, even though the percentage of the population is low, you got to go and find them. You can find environmental hazards are greater where people of color and poor people live. So it’s not just a southern thing. It’s not just a big city thing. You can also discover these issues in terms of the racial and class dynamics that make people in places more vulnerable.

So that judge who ruled that wasn’t discrimination did you ever get to face him and challenge that particular choice that he made? What happened in that particular situation?

The case was filed in a federal district court in Texas. This was 1979. I don’t know when you were born, what year were you born?

1983.

1979 and Texas in the deep south was not a time when federal judges wanted to see discrimination. So this is a time when the judge was calling the plaintiffs in the case “niggras.” “You niggras be quiet. I know what’s in that niggra neighborhood.”

And if you know anything about the South, if you’ll call a niggra, that’s, that’s tantamount to the N-word. The case went to court in 1985, and it was appealed to the fifth circuit, which is in New Orleans. We lost on appeal. This case, even with the evidence that we had, was too soon for us to win. Sometimes you are ahead of your time. If you look at the data that we had that I presented and push it out today, you would see that we would probably win that case. I’ve testified in cases after 1985 and we won cases. We’ve stopped facilities from being built.

But again, 1979 and 1985 was just too soon. We could not get any environmental groups to help us. When I showed them that data, I told them what the research was. One white group leader said, “Well, isn’t that where the landfill is supposed to be?” We went to one of the oldest civil rights organizations, the NAACP. Again, this is 1979, and we were told, “We don’t work on environmental issues. We do housing discrimination, education, employment and voting.”

And so it took almost two decades before the environmental movement and the Civil Rights Movement got it and understood how these things are connected. There is still some hesitancy from some environmental groups and conservation groups to embrace or even address systemic racism regarding environmental protection. I’m talking about 30 years ago. When it comes to environmental protection, we’ve made a lot of progress, but we still got a long way to go.

What are your thoughts on Eugene?

I’ve been to the University of Oregon at least half a dozen times. Oregon is very different from Texas, Alabama, and Georgia, where I’ve done most of my work. But again, issues around environmental justice are not limited to any region or any state. I know there are environmental justice issues in Oregon. I know groups are working on environmental justice in Oregon. I’ve worked with a couple of professors in Oregon. I know that housing, residential segregation, (law) enforcement, and access to environmental amenities, this is not just unique to cities outside of the Northwest. Or the West. These issues are pervasive across. Even looking at a city like Portland, you can map where the most environmentally sensitive areas are. And map where people of color are. I would suspect that you would find greater vulnerabilities in terms of environmental stressors in those areas where you have the highest concentration of people.

Do you have a statement that you’d like to give to people who might not be familiar with you or your work? What would you like to tell them?

Well, I’d like to say to the folks concerned about the environment and concerned about justice: Our environmental justice movement was very methodical and targeted, addressing environmental issues that impact poor people and people of color, and marginalized communities. We are unapologetic about our quest for a clean and healthy environment for all. Just because you may not have a lot of money or maybe physically located in a neighborhood that may not be the wealthiest, that does not mean that you and your residents don’t have a right to a clean, healthy, nourishing environment that is sustainable for you and your family, relatives, and future generations. That’s what we fight for. That’s what we are working for. And that’s what keeps me going in terms of trying to make a difference. I do believe that one person can make a difference. If you work as a collective and an organization, you can make things better for all.